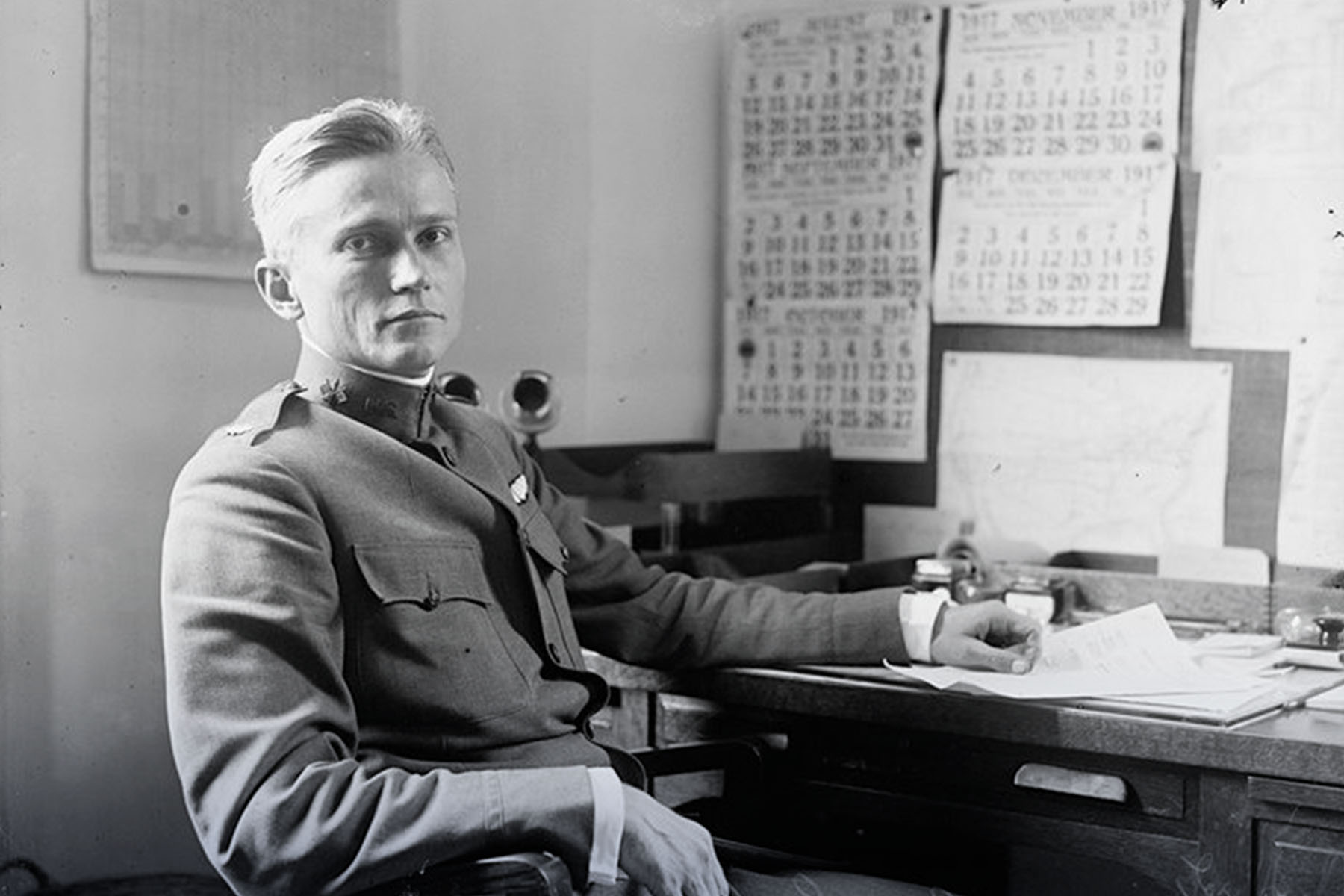

Hiram Bingham, the renowned explorer and historian who revealed the mysteries of Machu Picchu to the world, personified both discovery and perseverance. Whether you're a history buff, an adventure enthusiast, or simply curious about the man behind one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century, this blog offers in-depth analyses, captivating stories, and detailed explorations. These bring Bingham’s legacy to life.

Uncover untold stories, explore unseen photographs, and learn how Hiram Bingham’s expeditions have shaped our understanding of the Inca civilization. Don’t miss a single post—dive into the history that continues to inspire adventurers and scholars alike!

Who was Hiram Bingham?

Hiram Bingham III was born on November 16, 1875, in Honolulu, Hawaii. The son of Hiram Bingham Jr. and Clara Brewster, he came from a family of pioneering Protestant missionaries. Bingham inherited his forebears’ genuine desire to bring the message of Jesus Christ to distant cultures.

However, his legacy took a different path, leaving an indelible mark on the history of archaeology and exploration. Bingham passed away on June 6, 1956, in Washington, D.C., but his legacy as the discoverer of Machu Picchu endured, inspiring explorers and scholars around the world.

Early life of Hiram Bingham

From childhood, Hiram Bingham found refuge in books and his vivid imagination. Initially, his parents only allowed him to read the Bible and a green album of moral tales. Over time, he found sanctuary in the Honolulu library, where he devoured all kinds of readings, falling mainly in love with Mark Twain’s "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn."

At 16, he returned to the United States to study at Phillips Academy in Massachusetts, a prestigious prep school in Andover, hoping to follow in his father’s footsteps. He graduated with a degree in business administration from Yale University in 1898 and then moved to Berkeley to pursue postgraduate studies in Sociology at the University of California. However, he shifted his focus to history and completed his Ph.D. at Harvard University.

In 1900, Hiram Bingham's life took a dramatic turn when he married Alfreda Mitchell, the daughter of a distinguished family and heir to the Tiffany & Co. jewelry empire in New York. This marriage opened the doors to high society in America and provided him with the means to fund his expeditions and start his life as an explorer. By 1907, he had become a lecturer in history and geography at Yale University.

Hiram Bingham expeditions

Andean Expedition: Venezuela and Colombia, 1907

In 1907, Hiram Bingham led an expedition across the Andes of South America, exploring regions of Venezuela and Colombia. Bingham and his team followed the historic route of Simón Bolívar in his independence campaign, marveling for the first time at the vastness of the Andes stretching across the continent.

The breathtaking lake views and the captivating landscapes of South America captured Bingham's heart. As they traversed Venezuela, they encountered significant challenges, culminating in a visit to the tavern in the town of Agua Blanca. In Colombia, the beauty and complexity of the surroundings far surpassed Bingham's expectations, leaving him fascinated.

Discovery in Cusco: The Navel of the World, 1909

On January 28th, in Peru, Bingham arrived in Checacupe along with Clarence Hay, venturing into the Huatanay Valley at an elevation of 3,500 meters above sea level. In Cusco, he discovered an ancient megalithic settlement, explored numerous Catholic churches, and was captivated by the Incan walls and the University of San Antonio Abad of Cusco. He was astonished to find a university older than Harvard.

Later, he visited Sacsayhuaman, an Inca fortress whose vast and complex architecture left him astounded. He considered it the most impressive human-made work he had seen in America.

Adventure to Choquequirao: The Cradle of gold, 1909

On February 7, 1909, Bingham and Hay ventured northeast, reaching the Apurímac River en route to Choquequirao, known as the "Cradle of Gold." Following a narrow, twisted, and steep path, they uncovered the ruins of what were extensive agricultural terraces covered in vegetation.

As an Andean condor soared majestically above them, Bingham felt that Choquequirao was the most exciting site he had seen so far. The only issue was that Choquequirao was not the last Inca refuge; the actual final Inca city remained undiscovered.

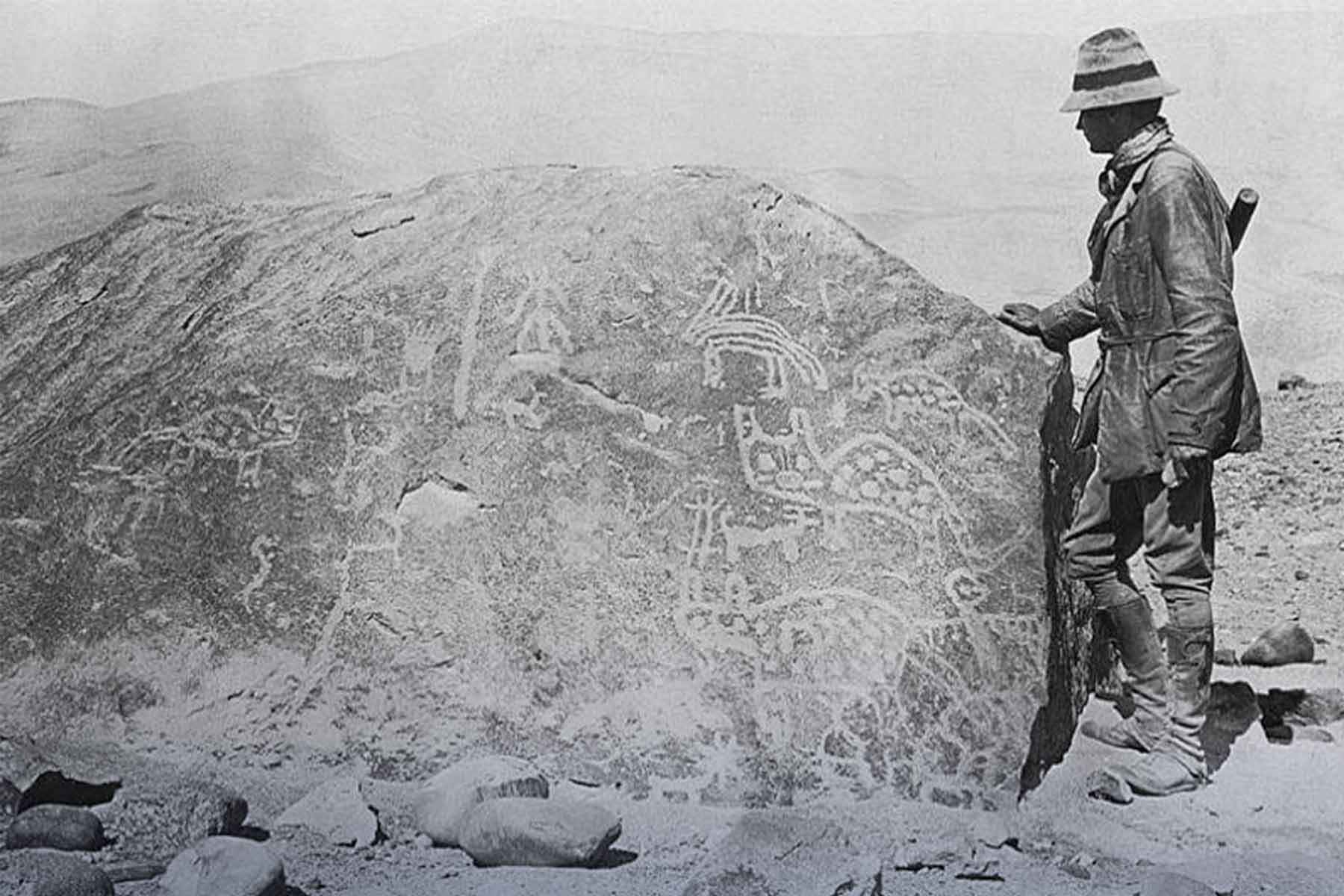

In Search of Vilcabamba: The Last Refuge of the Incas, 1911

On July 25, 1911, Hiram Bingham's expedition continued its quest for the kingdom founded by Manco Vitcos, as well as for Vilcabamba la Vieja, its sacred refuge. Descending the river to the indigenous village of Chaullay, they crossed a bridge and began their ascent along the Vilcabamba River. Their first stop was at the hacienda of José Pancorbo. Upon reaching Vitcos and Yuraq Rumi, Bingham encountered findings that left him with more questions than answers, revealing that much was still to be discovered about the last Inca stronghold.

The rediscovery of Machu Picchu

On July 19, 1911, Hiram Bingham began the search for a lost city hidden in the mountains of the Urubamba Valley. His expedition set off from the Cusco Valley, following the route of Manco Inca towards resistance, passing through the Yucay Valley, the sacred valley of the Incas, en route to Ollantaytambo. There, the group rested and camped. Captivated by the imposing fortress, Bingham explored and climbed the ruins, mesmerized by the view and declaring Ollantaytambo "a place worthy of pilgrimage."

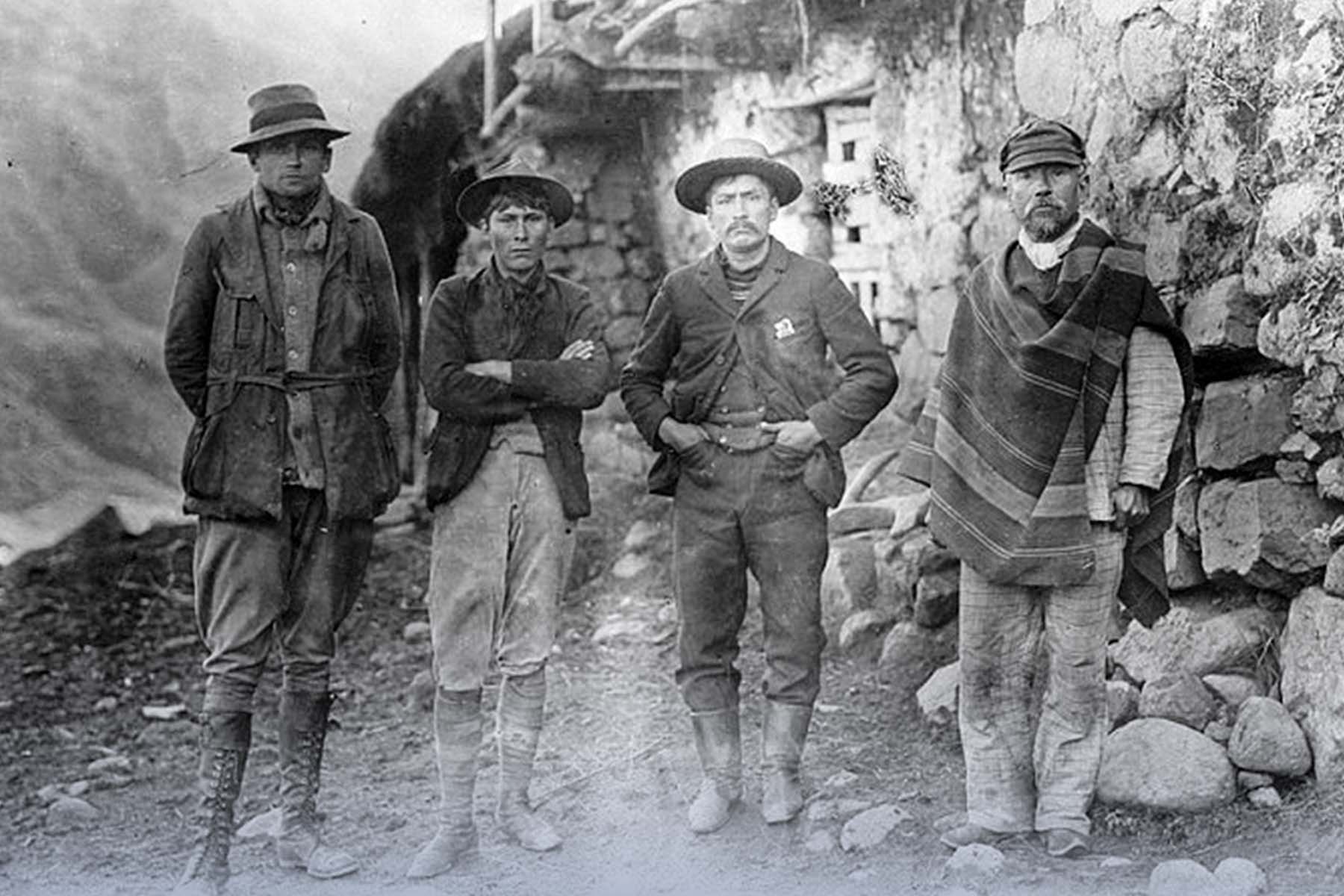

The next day, accompanied by Harry Foote, William Erving, Carrasco, two muleteers, and two porters, Bingham continued his exploration downstream towards Antisuyo, following the trail of the rebel Inca. The expedition traversed a true tropical forest and, after passing the Torontoy hacienda, arrived at Mandor Pampa. It was here that Bingham and Carrasco met Melchor Arteaga at a small house along the road.

Arteaga pointed them towards a high peak, Huayna Picchu, indicating the ruins across the mountain range. Although initially thinking he was too close to Cusco to have reached his initial targets of Vitcos and Vilcabamba, Bingham decided to document every site he visited. He hired Arteaga as a guide to climb the next day.

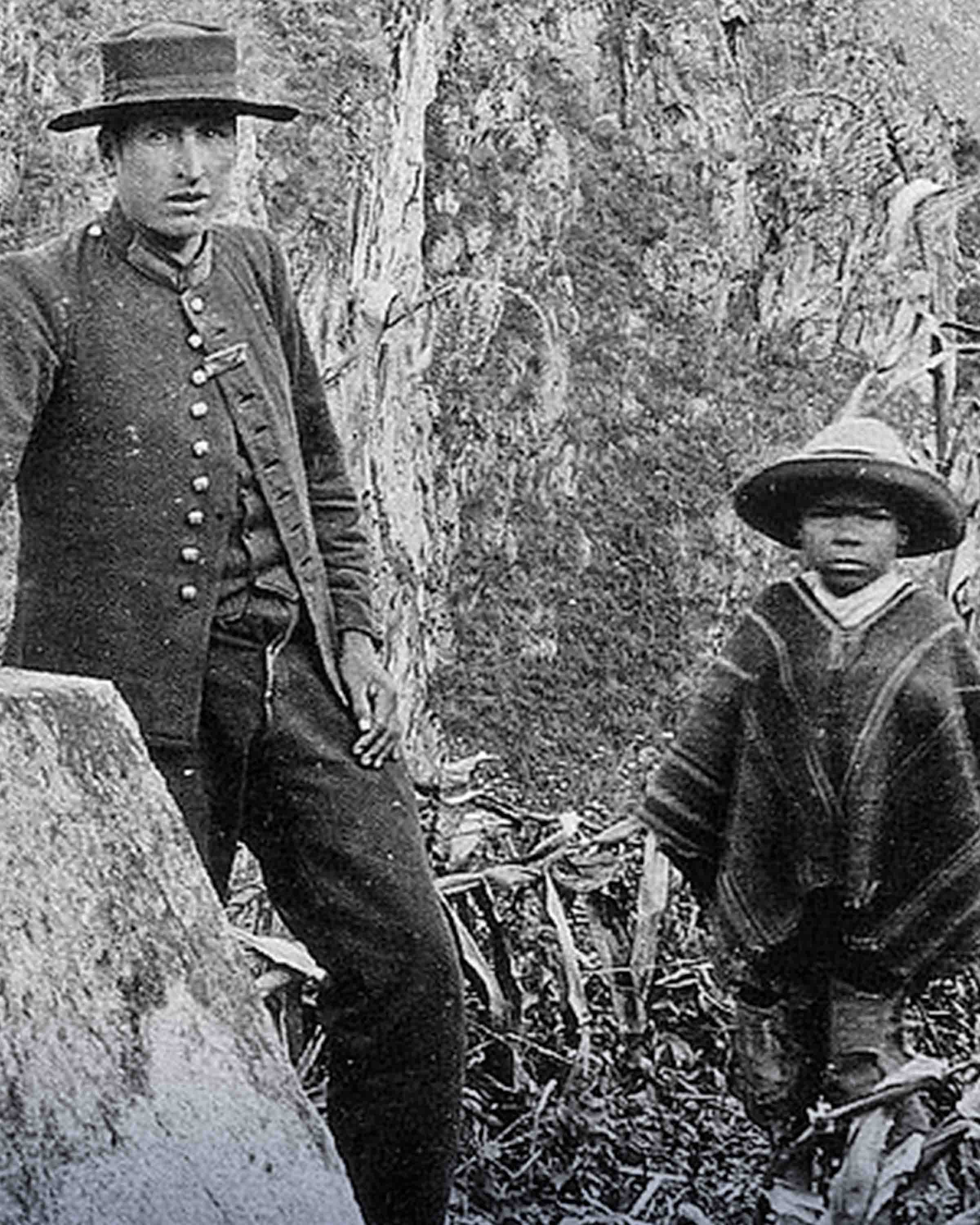

On July 24, 1911, despite the rainy and cold weather with low clouds, Arteaga, Bingham, and Carrasco departed from Ollantaytambo. They veered off the main path and pushed through the dense vegetation toward the river, where Bingham and Carrasco crossed a log bridge on their hands and knees. As they delved deeper into the jungle, the path grew steep and muddy, with raindrops dripping from the trees above.

Eventually, they arrived at a solitary cabin, the home of the Richarte family, farmers who had escaped the abuse of a landowner. For Bingham, this place held special significance. A tired Arteaga passed the task to Richarte and Anacleto Álvarez, who in turn entrusted the guide to Pablito, Richarte's young barefoot son, no older than eight, who led Bingham to the Inca structures.

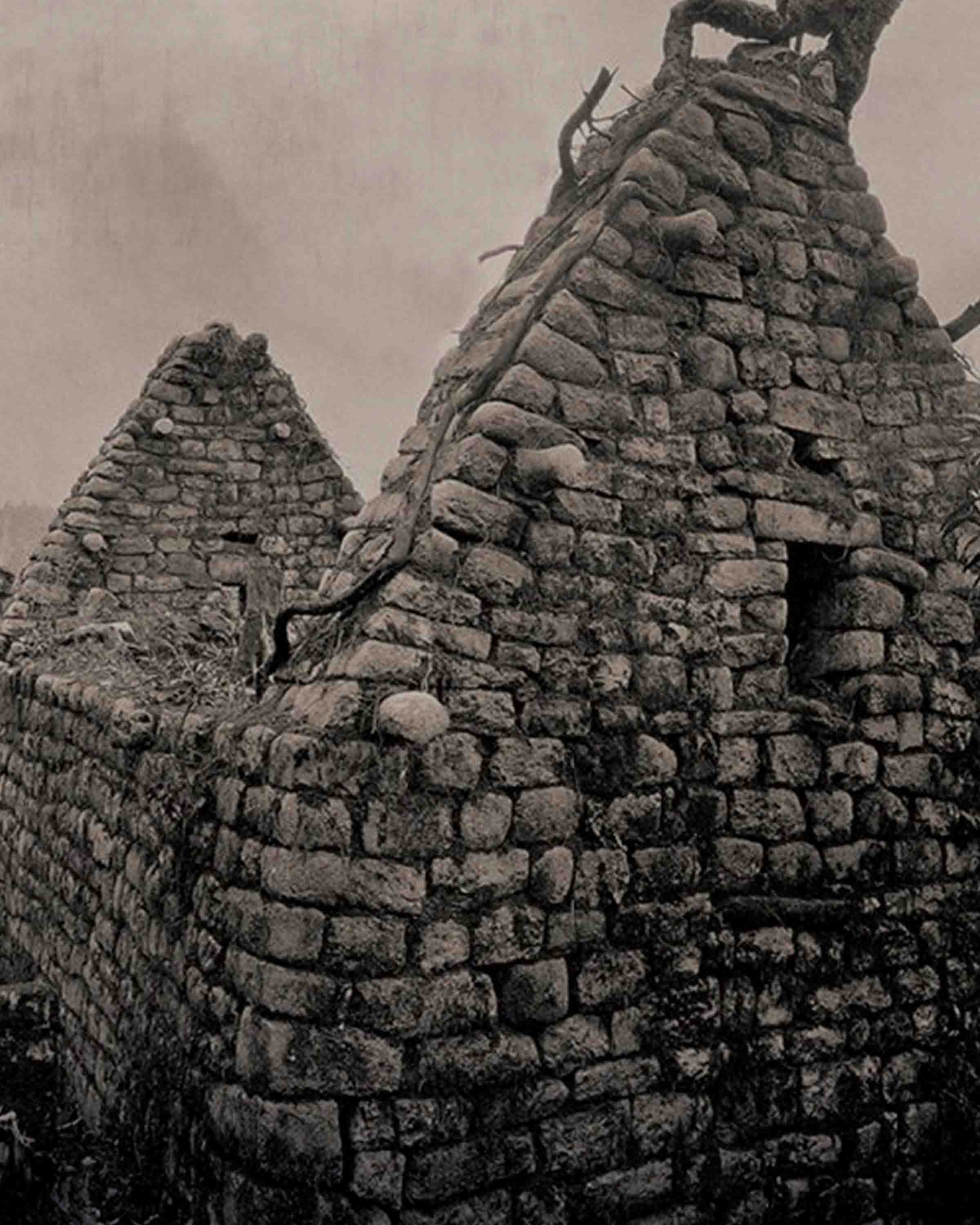

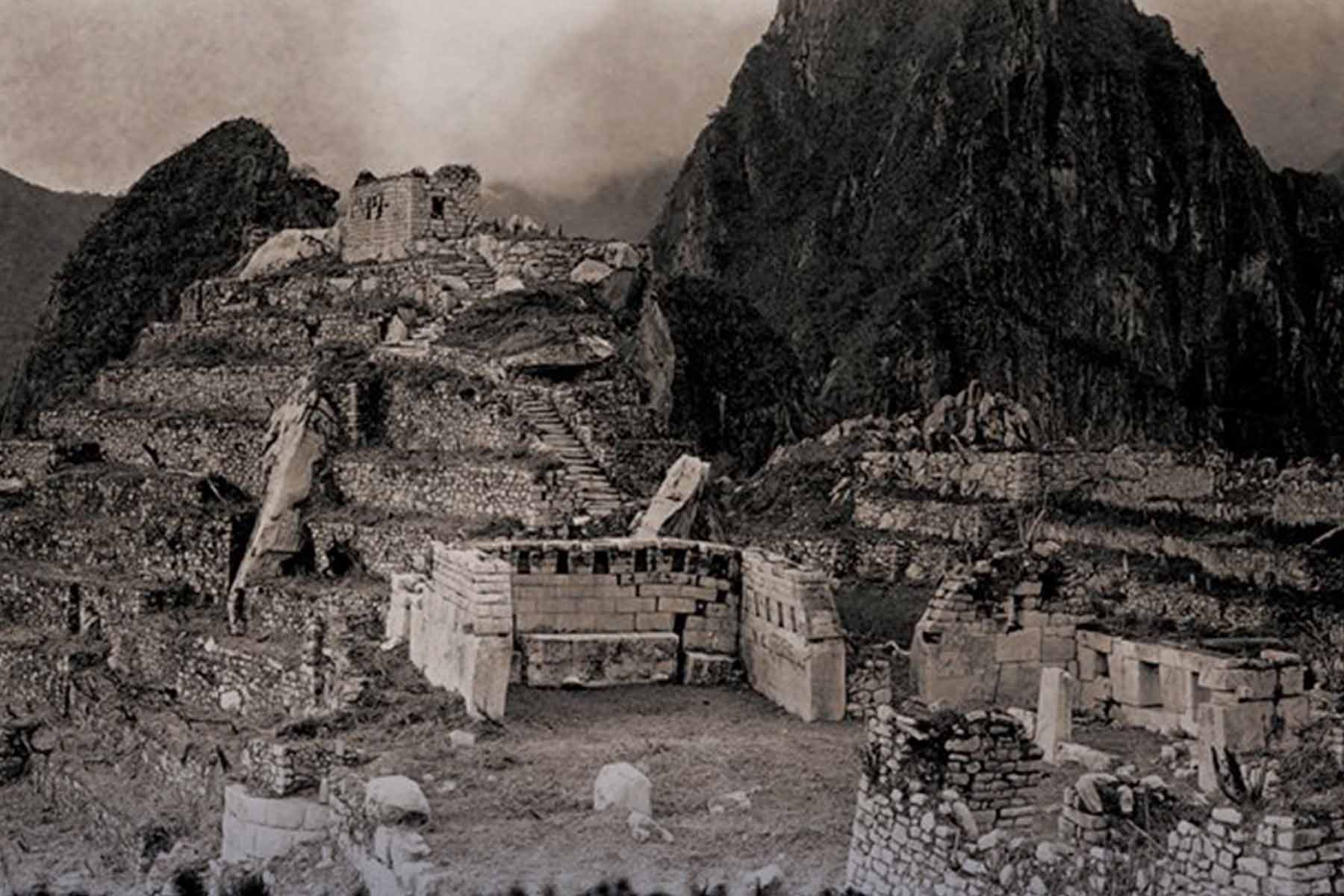

Upon first glimpsing the grand and impressive Huayna Picchu, Bingham was astounded by the enclosures he found. This moment marked Hiram Bingham's unveiling of Machu Picchu in Peru, an Inca city hidden beneath dense vegetation. He marveled at the architectural marvel of temples, fountains, and palaces perched on steep slopes. Bingham pressed on with his exploration and recorded the Intiwatana, a religious sundial that tracks the passage of seasons and sacred days.

Precursors to Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu

Before Hiram Bingham introduced Machu Picchu to the world, other explorers had already left their marks on the history of this enigmatic site.

In 1877, the German explorer Hermann Goering published a chronicle of his expeditions in the Urubamba Valley, where he documented a fortress at Picchu. In this work, he produced a cartographic document that presented the place names "Machu Picchu" and "Huayna Picchu" for the first time.

In 1880, Charles Wiener reported rumors about the existence of Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu, though he never visited the site himself. Later, in 1887, Augusto R. Berns organized an expedition aimed at looting Inca ruins near Torontoy, displaying a more commercial than scientific interest in the region.

Agustín Lizarraga, who in 1902 came to be considered by some as the true discoverer of Machu Picchu, left his signature at the Temple of the Three Windows, a fact that Bingham later noted and recorded in his diary. This evidence showed that Machu Picchu was already known to locals and that some scholars had even published previous works about the fortress.

- Finally, in 1904, the Peruvian Carlos B. Cisneros included in his "Atlas of Peru" the existence of the ruins of Huayna Picchu, contributing to the geographical record of these important archaeological sites before Bingham's arrival.

These backgrounds emphasize that, although Bingham played a crucial role in introducing Machu Picchu to the international academic sphere, the footprint of previous explorers also paved the way for the rediscovery of these iconic ruins.

Hiram Bingham, after the discovery of Machu Picchu in Peru

Following the discovery of Machu Picchu in 1912, Hiram Bingham faced accusations of wanting to monopolize Peruvian history, which triggered an intense debate in Peru about the management of its archaeology.

By 1915, Bingham returned accompanied by a team of specialists with the goal of clearing the forest and creating a detailed map of the Inca citadel. During this expedition, Bingham and his team conducted excavations both inside and around the enclosures. The team included engineer Ellwood Erdis and osteologist George Eaton, along with two local workers, Toribio Recharte and Anacleto Alvares. Together, they began the laborious task of removing the vegetation that covered the site and excavating Inca tombs.

Upon completion, Bingham spread the results of his exploration through an influential article in National Geographic magazine. With this, Hiram Bingham became the first person to recognize and promote the importance of Machu Picchu globally, significantly contributing to global knowledge about this iconic Inca citadel.

The end of an era of exploration

In 1922, after concluding his exploratory adventures and serving in the war, Hiram Bingham decided to retire from expeditions. Although already recognized as the scientific discoverer of Machu Picchu, he most enduringly introduced this impressive Inca citadel to the world, solidifying its historical and cultural significance globally.

7 Facts about Hiram Bingham

Hiram Bingham was an explorer and a politician. He was elected a U.S. Senator from Connecticut in 1924 and served until 1933.

During World War I, Bingham served as an aviator and reached the rank of lieutenant colonel in the United States Air Force.

Bingham was not only an explorer but also an innovator in teaching methods. During his expeditions, he introduced and developed aerial photography in archaeology, which transformed the way archaeological sites are documented and studied.

Although today he is globally known for discovering Machu Picchu, at the time, Bingham faced criticism and controversy for removing artifacts from Machu Picchu and taking them to the United States. This act sparked a prolonged debate and dispute between Peru and Yale University over the repatriation of these objects.

Interestingly, although Machu Picchu gained worldwide fame thanks to Bingham, he was not the first modern person to visit the site. Documents and evidence suggest that several locals knew about the existence of Machu Picchu long before Bingham "rediscovered" it in 1911.

Bingham wrote several books about his experiences and discoveries, including "The Lost City of the Incas," which is a vivid narrative of his discovery of Machu Picchu and remains a popular read for history and archaeology enthusiasts.

- It is believed that Hiram Bingham inspired the character of Indiana Jones, the iconic adventurous archaeologist created by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg.

Adventures into the unknown

Hiram Bingham was more than an explorer; he was a pioneer, an educator, and a public servant whose legacy continues to inspire generations of archaeologists, adventurers, and dreamers. As we close this chapter on Hiram Bingham, Machu Picchu, and Peru, let's open our hearts and minds to the lessons taught by both the stone ruins and the stories of those who discovered them.

Venture beyond the known, and who knows what discoveries you might make. Until next time!

Add new comment