Baked treats, offerings, and acts of love that transcend time and even life? Similar to other countries worldwide, the Day of the Dead in Peru is a significant celebration, uniting families in a serene and faithful tribute to their ancestors.

Discover how Peru celebrates the Day of the Dead, how ancient cultures understood death, and how those beliefs live on in modern customs. We’ll explore offerings, traditional foods, breads like t’anta wawa and pan caballo, music, cemetery traditions in Cusco, and traveler etiquette, so you can participate respectfully and connect more deeply with this unique celebration during your visit to Peru.

When is the Day of the Dead in Peru?

In Peru, the Day of the Dead is observed annually on November 2nd, immediately following All Saints' Day, that typically includes an additional religious mass held on the subsequent Sunday. The Day of the Dead has deep, pre-Hispanic roots, making it a perfect example of cultural resilience.

A glimpse at death in Peruvian culture

The Day of the Dead in Peru cannot be understood without understanding the perception of death throughout history. We will take a brief look at how this subject, which is related to every culture in the world, was viewed by the ancient Peruvians.

Pre-Inca roots: Dead and Fertility

In ancient Peru, death was perceived in a completely different manner from the Western concept. Death was seen as part of an infinite cycle where the soul continues to inhabit the body even after physical death, in turn bestowing fertility and good fortune. This characteristic is evident in the imagery of the Nazca culture (famous for the Nazca Lines), which developed between approximately 100 BC and 800 AD in the area south of Lima.

Archaeological remains show graphic representations of trophy heads, the result of fierce conflicts of that era. Researchers have found them both as mummified heads and in painted scenes. Interpretations of these pieces point to a ritual vision in which death carries power, sustaining life and fertility.

Inca Period: Uyway and Mallkis

During the time of the Inca, the dual and cyclical concept of life was maintained, where death was not an end but a continuous part of existence. This is also reflected in the division of the Andean world into three spaces: the upper world (Hanan Pacha) where the gods dwell; the present world (Kay Pacha) where the living reside; and the lower world (Uku Pacha) where the deceased ancestors, known as mallkis (mummies/ancestor and root) , are found.

Living alongside the human remains of ancestors was common throughout the Tawantinsuyu. Ayllus (families) engaged in a reciprocal act central to Andean values, called "uyway," which involves the mutual care and "raising" of both the living and the dead. Daily activities included sharing food with the mallkis, with offerings such as chicha (corn beer), coca leaves, and dishes made with cuy or llama, seeking in return health, vitality, and fertility for the community.

This practice was not reserved for a single day, as it is today, but was a daily task. The relationship of the mallki as the root, origin, and seed of a family (ayllu) was highly valued by the hierarchy, with the oldest ancestors being the most venerated and referred to as "Machula Aulanchis" (our old grandfathers).

Many of these remains were dressed and shared space with the living, or rested in huacas (sacred places) and chullpas (funerary towers), where their descendants visited them. They were even carried in procession around Cusco’s Plaza de Armas, a tradition later reinterpreted through the Christian celebration of Corpus Christi.

Colonial and Republican Period: Burial and Exhumations

Following the Spanish conquest, the veneration of the mallkis was forcefully eradicated during the Extirpation of Idolatries in Peru. This campaign systematically destroyed sacred huacas and, along with them, the centuries-old mallkis (Machula Aulanchis) that had been preserved there. This was a critical blow to the ancient Peruvians, who believed the physical body was necessary for the ancestor to coexist with them in this plane and thus maintain their memory.

With the Church and evangelization established throughout the territory, the practice of burial was instituted. These burials were forbidden from being accompanied by excessive offerings or ancestral liturgical elements like food and clothing. Burials were conducted near Christian temples and churches, and often even inside them (especially for wealthy families and church members). This was due to the Christian belief that placing the body closer to the main altar would ensure spiritual protection and a better position on the Day of Final Judgment.

Peruvians struggled to adopt these new practices. With their ancestors' bodies buried, they felt they could no longer care for and feed (uyway) them. They believed their ancestors would be forever trapped and enclosed, cut off from their family, their huacas, and nature. This resistance cornered Peruvians into practicing the clandestine exhumation of bodies. The oldest documented record of this dates to less than 10 years after the arrival of the Spanish. Due to the persistence of this practice, the First Council of Lima established public punishment: 50 lashes and 3 days in prison.

Cultural resistance continued, slowly weakening as evangelization spread across America. It is said that when burial was unavoidable, mourners would sometimes collect the hair and fingernails of the deceased, possibly to take them to their homes or huacas. The final records of the ancestral practices of uyway, mortuary cults, and the interaction of Indigenous people with mummies persisted until the 18th century.

Did the Incas celebrate the Day of the Dead?

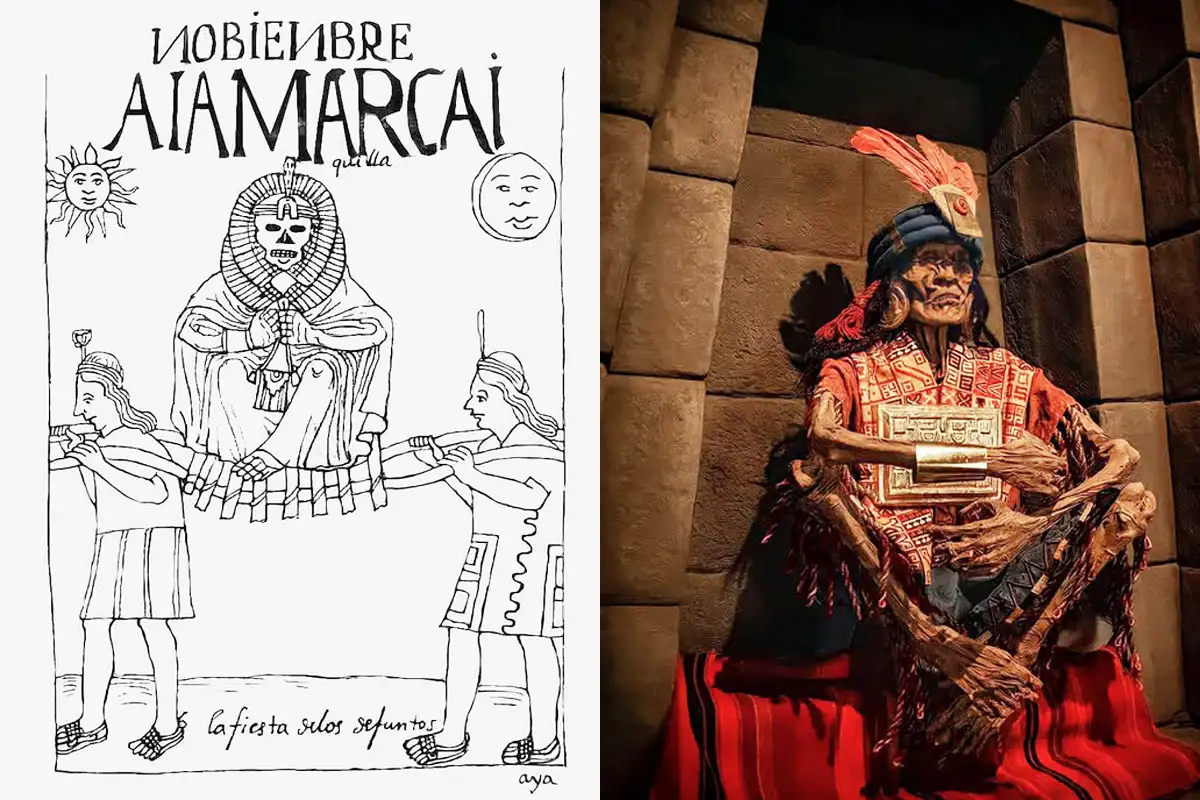

After this historical overview, it is clear that, in Inca times, practices related to death were part of daily life. In the Inca calendar, November corresponded to Aya Marcay Quilla, a month devoted to honoring the Inca emperors’ mallkis and offering them ritual care. During the colonial period, these cycles of remembrance were aligned with the Catholic observances of All Saints and All Souls.

Modern Period: Syncretism

Despite the events of the past, the practice of uyway can still be seen today, different in form, but guided by the same purpose: to live with, share with, and care for our ancestors, if only for a day, as though they still walked among us.

In Perú, families begin preparations days earlier, coordinating travel and organizing the logistics of the celebration. Peruvians flock to cemeteries, transforming them into vibrant centers of remembrance. These solemn rites are beautifully interwoven with Andean traditions: families pour chicha as an offering for returning spirits, and the actions themselves echo ancient offerings to the earth. Meanwhile, coastal cities favor celebratory family reunions held directly near the tombs. Across all regions, Peru's Day of the Dead is a striking display of resilient syncretism.

Sounds, Flavors, and Togetherness in the Day of the Dead in Peru

Relatives share home-cooked dishes and pour small toasts for their ancestors. Following the ancient tradition of reciprocity, they taste the food first, then invite neighbors and friends to join. Musicians circulate throughout the cemetery, playing traditional Andean huaynos and requesting musical dedications at specific tombs.

Priests move between the graves, offering blessings and leading prayers that punctuate the music and conversation. The day is filled with laughter and storytelling, recalling the journeys, jokes, and community milestones of the deceased.

Altars and offerings: coca, chicha and bread

Altars appear in the family home and the cemetery during November observances. Families arrange flowers, coca leave and meals with careful intention. They display photographs and favorite foods to greet returning spirits.

- Coca leaves: The coca leaf symbolizes reciprocity and respectful conversation with the dead. Elders carefully form k’intu bundles (three leaves) and raise them in quiet thanks. Participants place the leaves near photos, asking the ancestors for guidance and health.

- Chicha: This traditional corn beer bridges Andean memory and community hospitality. Families pour small libations directly onto the earth before sharing sips together. They also reserve a cup for the honored ancestor at the altar. Depending on the tradition, other forms of alcohol preferred by the deceased, such as beer or pisco, may also be shared.

- Bread Figures and Food: Families buy bread figures and modest offerings. Occasionally, traditional seasonal baked treats are offered, always prioritizing the favorite foods and tastes of the deceased.

Day of the Dead in Cusco

Throughout this period in Cusco, special sweets and pastries are prepared and offered to the deceased, sometimes in miniature. The celebration also features delicious typical dishes, particularly those made with pork meat.

The Main Dishes of the day of dead in Cusco

- Lechón (Crispy Piglet/Roasted Pig): This central, substantial dish features piglet meat roasted to achieve a crispy skin and tender interior. It is frequently accompanied by tamales and cooked moray (white dehydrated potato). Cusco-style preparation of lechon distinguishes it significantly from versions found in other regions of Peru.

- Other Favorites: The altar will include the beloved dishes of the deceased, which in the Cusco region often feature Andean staples like:

- Cuy al Horno (Baked Guinea Pig)

- Chicharrón (Fried Pork)

Dead Bread: Bread Baby and Bread Horse

- T'anta Wawa (Bread Baby): This iconic offering, a slightly sweet, spongy bread dough, is shaped like a baby swaddled in a blanket. Its face is adorned with colorful frosting or candy, symbolizing rebirth and the beginning of life. It is commonly gifted to female children.

- Pan Caballo (Bread Horse): Bread shaped like a horse is a common gift for male children, symbolizing strength and health.

The Ritual: The T'anta Wawa is so central that fairs are held in its honor, and some families and communities host a symbolic "Baptism of the Wawa" as a fun, festive tradition.

Baking and Sharing: The Giant T’anta Wawa

In Cusco, this tradition starts each November, featuring large, highly-attended events dedicated to the creation and presentation of the giant T'anta Wawa. This massive bread figure is ultimately sliced and shared among all those present, symbolizing communal unity.

Sweets in the Day of the Dead in Cusco

From t’anta wawa to tiny confections, these traditional treats, available at San Pedro Market and local bakeries, honor ancestors and bring families together at altars and graves during festive celebrations.

Baked Treats Name | Description |

| Maicillo | Maicillo is a small, delicate cookies crafted primarily from organic cornmeal, lending them a rich, golden color and a uniquely soft, crumbly texture. Be mindful, however, as they are highly fragile and must always be enjoyed alongside a beverage to prevent them from drying out the mouth. |

| Empanada Dulce | The empanada dulce is a sweet, flat baked pastry characterized by its crisp yet tender texture and distinctive oven-baked aroma. This iconic treat is beloved by all and makes the ideal companion for a shared moment of simple joy. |

| Rosca | This is a delicately sweet biscuit, baked in the shape of a small ring or round. It stands out for its exceptionally dry, tender texture. With its simple, appealing flavor, it's the perfect sweet treat for those who prefer subtle indulgence. |

| Suspiro | Meet the ethereal Meringue Sigh (Suspiro), a sweet treat defined by its delicate, melt-in-your-mouth lightness. Visually stunning, they are presented in a colorful array, including pink and yellow, pure white, and aromatic coffee-flavored brown. Be warned: their intense sweetness means a little goes a long way, so enjoy these treats sparingly! |

| Bizcocho | A delicate, cloud-like sponge that is incredibly soft and tender. It offers a gentle sweetness, often complemented by the distinctive note of anise. Since it’s so light, this treat is the perfect choice for those who prefer an easy-to-digest dessert that satisfies without being cloying. |

| Condesa | It is a delicate, handcrafted butter biscuit celebrated for its elegant simplicity. With a lightly sweet, crumbly shortbread texture, it often carries a subtle savory note from sesame seed topping and is sometimes decorated with candy sprinkle that add a festive crunch and visual delight. |

Note: In recent years, these miniature versions of traditional pastries have been crafted and sold specifically for placement on ofrendas (altar offerings).

How to participate in the day of dead in Peru

Taking part in this celebration is a fully immersive experience. It's essential to understand and respect the local culture, including the unique customs of each family, whether in their homes or at the cemetery.

Travel tips:

- Arrive early and observe how families organize the space.

- Dress modestly and layer up: Closed-toe shoes, a light jacket or shawl, and sun protection keep you comfortable all day.

- Bring Peruvian currency (soles): Many vendors sell food, flowers, and offerings near cemeteries, and cash is preferred.

- Follow posted rules and ask caretakers or elders before entering family gathering areas

- Request permission for photos: Say “¿Puedo tomar una foto?” Avoid flash, children’s close-ups or capturing images during prayers.

Traveler etiquette:

If any family invites you to be part of this celebration, feel fortunate because you will be able to observe this ancestral celebration firsthand. Follow the next recommendations during the gathering, meal and celebration:

Before the gathering

- Don’t arrive empty-handed. Ask what to bring (meals or beverage). They might modestly say you don't need to bring anything, but it's always best to bring something to share.

- Confirm details. Double-check time, meeting spot, and any family preferences about food or dress.

During the meal

- Observe the first toast. Typically, a small offering of liquor is poured for the Pachamama (Mother Earth) before drinking, but not all families follow this custom. If they do, wait a few minutes to see and then respectfully follow suit.

- Share what you brought. Hosts place large platters at the center for everyone. If you bought any food or drink to share, this is the time to present it.

- Let the elders go first. It’s tradition to serve the elders first, then move on to the rest of the guests without anyone needing to ask—just be patient and wait your turn.

During the celebration

- Match the pace. Some families are very spirited and outgoing, while others are more quiet and thoughtful, or they can be both. Remember they are happy to see their loved ones again, but there's often a feeling of nostalgia too.

- Speak softly. Let family members lead the conversation, sharing stories and memories of their departed loved ones. Listen with care, you’ll come to understand the deep affection they still hold for their ancestors.

- Accept invitations kindly. If you're invited to dance, join in for a moment, connect with others and let their energy lift you. It's also perfectly fine to politely decline

Wrapping up

- Thank you everyone. Say goodbye to elders and offer a respectful farewell to the deceased at the altar or niche.

While you are here in Peru or exploring the wonders of Cusco, we encourage you to pause and connect with the profound, collective emotion of the Day of the Dead. Indulge in the rich traditions, the delicious gastronomy, and the unique environment. Embrace the local culture and allow yourself a peaceful moment to connect with your own spirit and your ancestors.

Remember, travel is a continuous journey of self-discovery and reflection. Don't let this experience end here! Complement it with more activities to fully embrace your vacation. We are ready to assist you in crafting the perfect trip.

Day of the Dead Peru FAQs

How is Peru’s Day of the Dead different from Mexico’s?

In Peru, the focus is much more on graveside cleaning, making offerings, and holding family gatherings that blend Christian and pre-Hispanic traditions. Unlike Mexico, face paint and Catrina figures are extremely rare. The focus here is on Andean traditions and similar offerings like coca leaves, chicha (corn beer), and the symbolic t'anta wawa bread (a sweet bread shaped like a baby).

How does Peru celebrate the day of the dead?

Families visit cemeteries on November 1–2 to clean and decorate graves. honoring their departed loved ones with heartfelt offerings and shared food and drink. In the Andean regions, especially around Cusco, the day is marked by connection and remembrance. Typical offerings include coca leaves, chicha (corn beer), local treats, and the t’anta wawa (bread baby). Many spend the day at the cemetery playing music, praying, and even picnicking beside the graves..

Where can I experience the Day of the Dead celebration in Cusco?

To truly appreciate the unique, syncretic blend of traditions celebrated on this day, we highly recommend visiting the Jardín de la Almudena Cemetery. Conveniently located less than 2 kilometers from Cusco’s main square, this historic site forms part of the UNESCO World Heritage designation of the city, offering a powerful glimpse into Peru’s layered cultural legacy.

What are the elements of the ofrenda in Cusco?

Families arrive with a variety of meaningful offerings, including flowers, candles, coca leaves, t'anta wawa or pan caballo (bread horse) bread figures, and the deceased person’s favorite meals and beverage. Personal items such as photos and small objects linked to the loved one are also frequently displayed.

In Cusco, this season brings a delightful array of traditional pastries sold locally, including condesa, maicillo, sweet empanadas, and suspiros. Be sure to taste these unique local foods. Crosses, rosaries, textiles, and incense appear based on family custom.

How long do you leave the ofrenda up?

Most families keep it from November 1 to November 2. Some extend it through the weekend. In cemeteries, perishable offerings are removed one or two days before.

What foods might I see on the day of the death in Peru?

Get ready to savor traditional dishes like pachamanca (earth oven barbecue), lechón (roast suckling pig), cuy (roasted guinea pig), chicharrón (crispy fried pork), etc. A variety of pastries and seasonal fruits are also enjoyed. True to custom, nobody eats alone. People happily offer small tastes of their food to neighbors and visitors, as a gesture of community and goodwill.

What is the etiquette for toasts in Peru?

Hosts usually offer the first small serving to the Pachamama. At this point, pause and wait for the family to toast.

- Observe the Offering: Watch to see if the family performs a Pachamama offering by pouring a bit of the liquor onto the ground. If they do or don´t, respectfully imitate them.

- Wait for the Toast: Wait for the family to make a toast before you sip your drink.

Will there be music?

Yes, huaynos (traditional Andean music), songs, and brass bands circulate respectfully. Families request dedications at specific graves. Musicians pause for blessings and prayers when asked.

Can travelers participate?

Yes, Always observe first, then gently follow the local cues. Always ask permission before taking photos. Most importantly, if you are invited to join a family's home celebration, be exceptionally courteous and respect their particular traditions.

What should I wear and bring?

Dress modestly and wear sturdy shoes. Pack layers for highland mornings and a light jacket for evenings. Carry small bills, water, tissues, and a reusable bottle of water.

Is it family-friendly?

Yes, children help clean niches and arrange flowers. Keep them close and explain basic etiquette. Most importantly, please avoid letting kids climb on tombs or decorations, or touch and play with the offerings.

Is photography allowed in cemeteries?

Only with clear permission from families or caretakers. Avoid flash and keep distance during prayers. Drones are not appropriate in these spaces.

Do I need a guide?

While not mandatory, having a licensed local guide is incredibly helpful for introductions and context. They offer valuable insight into the history, symbols, schedules, and local etiquette, ensuring you navigate the customs without a misstep. Plus, if your guide lives in the area, you might receive the unique honor of being invited to their family's personal celebration!

Why is sadness not allowed on the day of the dead?

Grief is natural, but the occasion emphasizes reunion and gratitude. Families prefer a warm tone that honors life and memory. Songs, stories, and shared meals help keep the atmosphere hopeful.

What do Peruvians do when someone dies?

Families hold a velorio, then a funeral service and burial or entombment. Communities often pray a nine-day novena, plus month and year memorials. Relatives bring flowers, candles, and food to support mourners

Add new comment